Shared from the Canary 3 March 2023 — part three of three reports by Steve Topple — thank you!

This is the final article in a three-part series looking at adoption in the UK in relation to mothers and caregivers. Part one, which you can read here, looked at how forced adoption is not a thing of the past – with high numbers of children forcibly removed from mothers by social services. Part two, which you can read here, looked at how systemic racism and ableism pervades the misogynistic UK adoption industry.

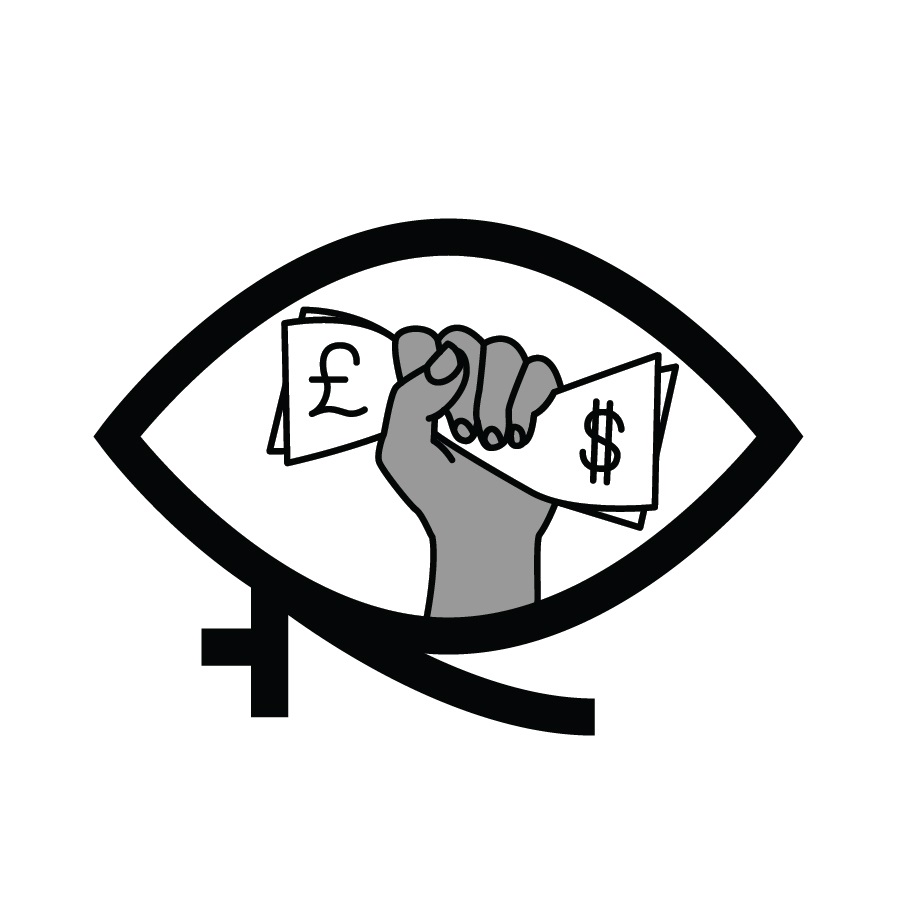

Adoption in the UK is an industry where children are worth huge sums of money to private companies. The state-sanctioned services who carry out adoptions run on racism, ableism, classism, and misogyny. More specifically, the tactics agencies use to forcibly remove children from chronically ill and disabled mothers are some of the most despicable imaginable. Meanwhile, the private companies running the industry are making tens of millions in profit. So, what price for a mother and child?

Allegations of fabricating illness

When a mother is chronically ill or disabled, her experience in family courts regarding residency of her child/children, or adoption, is often laced with prejudice, ableism, and misogyny. Tracey from campaign group Disabled Mothers’ Rights Campaign told the Canary:

Disabled mothers in family court face multiple prejudices. For example, 70% of learning disabled parents have their children removed, even for mild issues. In other cases, disabled mothers and disabled expectant mothers are disproportionately investigated by social services – with their children being removed.

Disabled mothers with invisible disabilities such as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), as well as autistic mothers, are disproportionately likely to have their children removed – despite their children often having the same condition. Social services blame the children’s ill-health on their mothers, who are wrongly accused of harming their child by projecting their own disability onto their children (Fabricated or Induced Illness, FII).

FII is an under-researched area, but what few statistics there are back Tracey’s assertion up. The majority of accusations of FII are false. Further to this, social services also use the potential for future harm as a reason to forcibly remove children from mothers.

The ‘possibility of future harm’

Journalist Cherry Casey spoke to Lisa from Disabled Mothers’ Right Campaign for Prospect, noting she:

had her daughter adopted against her will in 2005… Lisa knew she needed support, in her case due to complex needs including mental health issues and physical problems which meant she depended on crutches. She argues that while her mental health was a focal point during assessments of her parenting, her physical health, and the support she needed to cope, were never properly considered.

After several assessment centres – one where she was advised not to use crutches, later leading to a bad fall – her daughter was eventually placed for adoption aged two-and-a-half. Later, after Lisa was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, she was able to open an out-of-time appeal. “I was diagnosed using the symptoms I had been complaining about [throughout her various assessments]… and it was ruled that social services had acted improperly by not taking my physical needs into account and that if [they had] I may have been able to retain custody.”

The adoption, she adds, was not based on evidence that her daughter had come to harm while in her care, “but the possibility of some form of future mental, physical or emotional harm.”

As Tracey told the Canary, the state will also argue that the child’s future wellbeing as an adult is a reason to remove them from their mothers:

It is assumed that when a child whose mother is disabled grows up, they will inevitably become their mothers’ carer. However, if mothers were given their rights under the Care Act, a child would never need to become a carer. The fact is that it costs money to provide care in the community for disabled mothers and their children. After 12 years of austerity the money councils pay for support in the community has been reduced by 50% – whilst the money for forced removals has increased.

All this means social services and the state are systematically targeting Black, brown, and chronically ill and disabled women. It’s little wonder, though, given that care and adoption sectors are booming industries.

Feeding an industry to the detriment of mothers and kids

Tracy also told the Canary:

Millions are being spent on privatised children’s homes, fostering, and adoption. When a child is taken from their disabled mother and adopted, the financial obligation councils have under the Care Act to support mothers ceases. In short, they make a financial saving.

Private companies now dominate the landscape of children’s care. 80% of children’s homes are privately-run, and one in three children are fostered through a private agency. As the Guardian reported, private providers charge councils on average over £3,800 per child, per week for care accommodation. Meanwhile, fostering agencies charge on average £820 per child, per week. These industries turn profit margins of 23% and 19% respectively. Some of the largest companies are even owned by private equity firms.

The Transparency Project and journalist Martin Barrow investigated the adoption and care industry in the UK. They found that:

One of the largest [providers of children’s care homes] is CareTech, a company listed on the London Stock Exchange with a value of around £600 million. It pays dividends and buys up other providers in the sector, notably Cambian. Its senior directors are each paid £1 million a year, like directors of other listed companies. CareTech’s business has boomed during the pandemic; last year it was paid almost £430 million by local authorities and its profits rose 20 per cent to £60 million. The company uses a number of different names – Branas Isaf, Park Foster Care, TLC, ROC – capitalising on the ‘local’ credentials of the many former family-run businesses it has acquired over the years.

The smell of easy money has attracted an even more voracious business model: most of CareTech’s biggest competitors are private equity firms. These are mostly private partnerships based offshore in tax havens like Jersey and Luxembourg. You won’t find it on their websites but companies we know as National Fostering Agency, Polaris and Outcomes First are all owned by private equity firms such as Stirling Square Capital Partners, CapVest and August Equity.

This monopoly exacerbates already existing social inequalities:

It is increasingly common for one provider to have interests across all children’s service, from early intervention programmes through foster care, children’s homes, residential schools and mental health care. A child may bounce through the system, frequently changing homes and schools, based n decisions influenced by a provider with a financial interest in each move.

In the end, it seems the only people benefitting from adoption now are private companies and their shareholders.

Adoption: snatching children away from their mothers

Adoption in the UK is little more than a wholesale marketplace for children. It’s easy to see why those controlling it target marginalised children. When the price tag on a child’s head is £100,000, private companies will want the ones that either get them the easiest sales (dual heritage children) or easiest wins (children of chronically ill and disabled mothers who don’t always have the capacity to fight). Social services, medical professionals, and courts are complicit in this. They do the bidding of these private child snatchers without a thought for the impact on mothers and their kids.

It’s a damning indictment of state agencies, particularly largely inept social services, that forced adoption of children is so rampant. However, anyone with lived experience of social services knows they are invariably judgmental, classist, and not fit to be doing their jobs. Moreover, it’s utterly negligent of local councils who allow this to continue. Despite their protestations of funding cuts, they still have the power to control what their agencies are doing. At the same time, central government is also to blame for allowing the adoption industry to flourish in this toxic way.

However, the broader picture here is that we as a society allow this to go on. Adoption services serve as a mirror of the UK’s own prejudices of misogyny, racism, ableism, and classism. We live in a society where marginalised mothers are expendable. The state tells us (and we believe it) that their children are ‘better off without them’; that these kids will flourish with their new middle-class families, and that it’s the mother’s fault that they’re in this position in the first place. All of this is categorically untrue – yet this most evil of state-sanctioned industries continues.

Barely any attempt is made to keep children with their mothers, or to assist mothers with care plans and support. Ultimately, it shows the contempt that the government, adoption agencies, and society more broadly have for marginalised women.

Featured image via Disabled Mothers’ Right Campaign