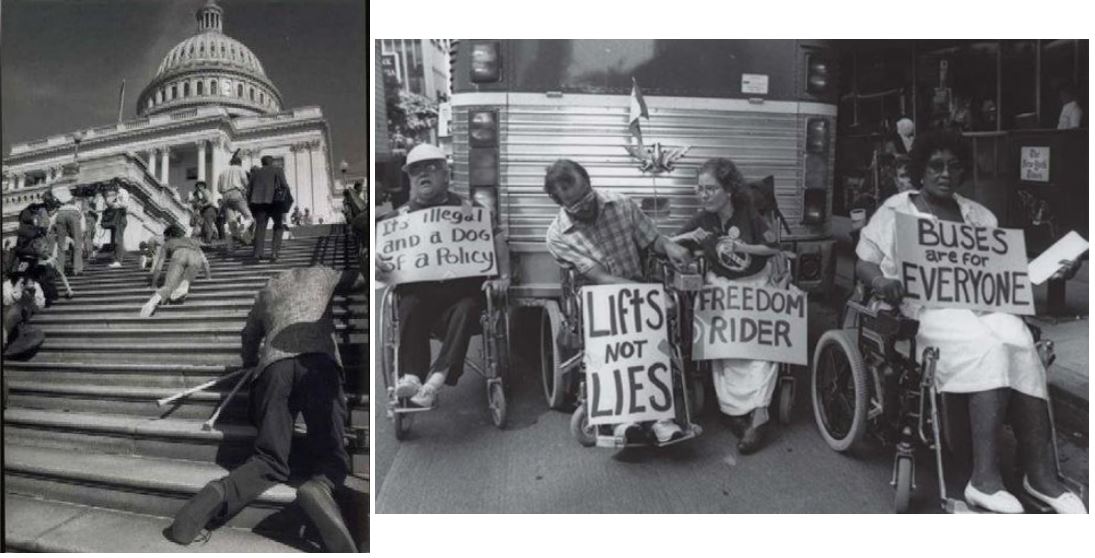

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) became law in July 1990. The success of the US disability movement — influenced by the anti-racist civil rights movement, women’s activism, and the demands of disabled Vietnam veterans like Ron Kovic, spurred on the UK campaign for anti-discrimination legislation. We won the Disability Discrimination Act 1995.

From the Washington Post, here is an opinion on the ADA and disability rights in the US.

———————————————————–

Made by History Perspective

Why disabled Americans remain second-class citizens

The big hole in our civil rights laws.

By David Pettinicchio

David Pettinicchio is a sociologist at the University of Toronto and author of “Politics of Empowerment: Disability Rights and the cycle of American Policy Reform.”

July 23 2019

“This month we celebrate the anniversary of the second-most important civil rights law in American history behind only the 1964 Civil Rights Act: the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA), which Congress passed in 1990. But while you might hear this law lauded [praised], you likely won’t hear about the wide-ranging efforts in recent years — mainly by congressional Republicans and the Trump administration — to undermine disability rights.

The attacks are widespread. Numerous Republican attempts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act threatened Medicaid funding that allows people with disabilities to receive in-home care. The Department of Justice is no longer enforcing accessibility requirements for websites or for medical equipment, making accessing online services far more inconvenient for disabled people and making doctor’s visits more of a hassle. The administration even urged the Supreme Court not to hear a case regarding accessible vending machines. These are just some of the most recent setbacks facing disability rights.

One possible reason these efforts aren’t front-page news: they are far from surprising. Disability rights have always been under siege. In fact, every time Congress has passed a law to protect the rights of disabled people, opponents have taken to the courts and the regulatory process to weaken the law, interpret it narrowly and create loopholes.

The result is a separate and unequal system of rights, one that dates to a failed attempt by advocates to include the disabled in the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Consequently, in practice, the disabled enjoy far fewer rights protections than other minority groups.

After the disabled were excluded from the Civil Rights Act, advocates in Congress kept fighting for protections, and eventually, hit on a novel strategy. In a bit of policy entrepreneurship, a group of lawmakers, mostly Democrats, successfully inserted language that made discrimination against people with disabilities illegal into the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which otherwise had nothing at all to do with civil rights.

But just as advocates were able to innovate, opponents waged a rear guard offensive, both from inside and outside government. Local transit authorities and the American Public Transit Association, as well as educational entities like school boards and the Council of Chief State School Officers objected, citing the costs of abiding by the new law. Many also warned that the law would give special treatment to one group while creating inefficiencies that undermined services for everybody else.

Through the 1970s, they found an increasing number of allies in Congress and eventually in the White House, thanks in part to the fact that virtually every member of Congress has local school and transit officials in their district. These officials and their congressional allies convinced the Carter administration to stall enactment of the regulations necessary to meaningfully implement the new law. Then, in 1979, in Southeastern Community College v. Davis, the Supreme Court struck an additional blow when it narrowly interpreted providing reasonable accommodations for the disabled, limiting what the law mandated.

This decision owed in part to how disability rights became law: excluded from the Civil Rights Act, and then squeezed into other legislation. Whereas courts have proven more deferential to the Civil Rights Act, they have largely been unable or unwilling to draw parallels between the disabled and other marginalized groups in discrimination cases, arguably finding it easier to rule against victims of disability-based discrimination because they are not ruling on this seminal legislation. The Supreme Court has been critical of, and even ignored, regulations, preferring a case-by-case approach quite different from the one the justices employ in handling racial or gender equality.

Negative court rulings motivated renewed activism throughout the 1980s. In 1989, fresh off his second presidential run, Jesse Jackson was among those calling for a new law to fix these problems, acknowledging that “Americans with disabilities do not receive the protection of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”

The result of this activism was the ADA, a pathbreaking law to be sure, but one that Congress itself had begun weakening immediately after it was introduced. Legislators wanted to build a broad bipartisan coalition — crucial for passage at a time of divided government — and assembling such a coalition required compromises, especially given lobbying by the public transit industry, among others, for looser restrictions. Even some ADA supporters, like John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Bob Dole (R-Kan.) wanted to narrowly define disability.

Ultimately, these compromises dashed the dreams of activists hoping for a law without loopholes. In the wake of the ADA’s passage, the pattern that had rendered the Rehabilitation Act less than effective repeated itself: compromise, retreat and unfilled promise coupled with inadequate regulations and narrow court interpretations characterized the struggle for disability rights during the 1990s and 2000s.

Compromise and retreat explain why, for example, so little has been done by Congress when it comes to community-based care. Despite a groundbreaking 1999 Supreme Court decision upholding the ADA’s provision that institutionalizing disabled people was discriminatory, and a bipartisan coalition led by Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) working throughout the late 1990s to shift Medicaid funding preferences from nursing homes to in-home care, real change hasn’t materialized.

By the mid-2000s, legislators recognized that the ADA, like its predecessor, hadn’t lived up to expectations. Once again, weak regulations and court decisions had proven damaging.

But proponents of a new effort to fix the ADA’s weaknesses hadn’t learned the lessons of why both the Rehabilitation Act and the ADA were so vulnerable. In an effort to overcome resistance, they again sought to cut deals with congressional opponents. And while they succeeded in passing the ADA Restoration Act in 2008, the process once again resulted in legislation with weaknesses easy to exploit.

And although Republicans have increasingly become the party opposed to disability rights, Democrats are not blameless in this pattern of broken promises and inertia that keep disability rights from being fully realized. For example, both Democrats and Republicans have effectively maintained a separate-but-equal vision of public transportation. Buying into the age-old argument that equal access for the disabled and program efficiency are mutually incompatible, Democrats have adopted policies that incentivize alternatives to accessible mainstream transit [public transport].

Without either party as a true champion, time and again, compromises made for political expediency have undermined disability rights and produced legislation that is vulnerable to being watered down. And opponents have whittled away at every piece of disability rights legislation. The result has been devastating for disabled Americans.

Today, civil rights are under assault as the Trump administration shows craven disregard for people with disabilities — along with its attacks on immigrants, people of color and LGBTQ people. As we mark another anniversary of the passage of the ADA, it is critical that people recognize that rights for the disabled are human rights. People with disabilities, like all members of our communities, should be ensured access to the same protections and opportunities.

Disability rights must be understood as fundamental and legislators must stand firm and unwilling to compromise away crucial provisions. What is needed are the continued efforts of movement activists and legislators interested in genuine positive reforms — those who appreciate the lessons of this 55-year cycle of policy innovation, retreat, citizen mobilization and policy restoration. Otherwise, discrimination and segregation will persist.”

Note: Disability movement photos added by WinVisible from here, George Bush should not get the credit!

,

1 thought on “Disability rights in the US — then and now”